With public and policy sentiment turning towards the idea that people with developmental disabilities deserved the right to care in their communities and a full life with control over their choices, a new system needed to be built from the ground up.

This law broke the Department of Mental Health and Corrections into two separate agencies.

The Legislature passed a law into statute requiring the Department of Human Services to provide in-home and community support services for adults with long-term care needs.

The new law gave a bit more freedom for marriage, but still denied anyone “impaired by reason of mental illness or mental retardation to the extent that he lacks sufficient understanding or capacity to make...responsible decisions” the right to marriage.

Governor Brennan appointed a “Task Force on Long Term Care for Adults” to study the systems of long term care as they stood and bring back policy recommendations to the administration.

Neville Woodruff, the lawyer who represented Pineland residents in the lawsuit, threatened new suits against Pineland saying, “They are very far behind in three major areas - staffing, quality of programs, and staff training.” Court Master Gregory was critical of the lack of improvements at Pineland as well, saying residents were “still just being kept. Life for them is purposeless."

The state decided to settle the lawsuit, rather than go to trial. The result was a two-part consent decree that detailed rights of persons with developmental disabilities at Pineland and in the community.

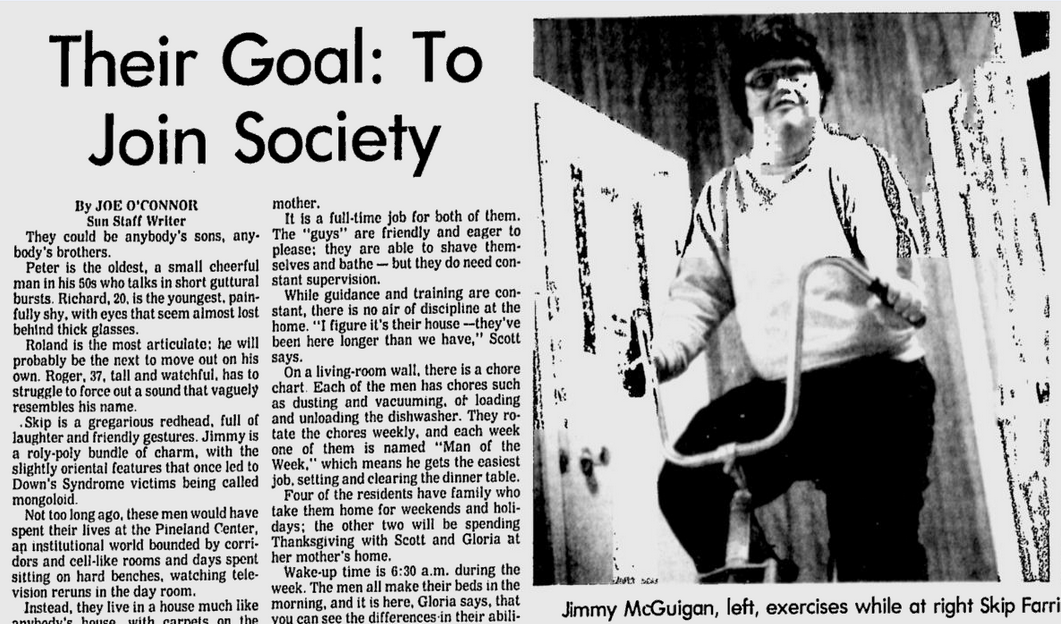

The years while the lawsuit worked its way through the courts were marked by much upheaval and many changes at Pineland. Many policies were beginning to be implemented in order to give Pineland residents more autonomy, choice, and opportunities.

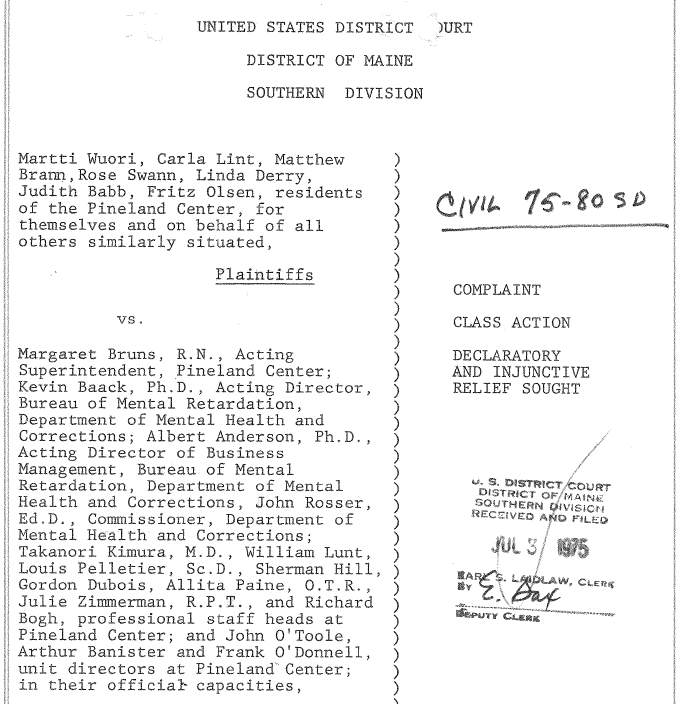

Pine Tree Legal Assistance, the first organization in Maine to provide free legal assistance to those in poverty, filed in federal district court in Maine on July 3, 1975 the lawsuit Wuori v. Bruns, alleging that the six defendants named in the case, and the "class" – all other residents and future residents – were not getting "training and education which would enable them so far as possible to lead normal lives."

This law provided clearer definitions of developmental disabilities that included specific conditions and specified that the conditions originate before the age of 18 (raised to 22 in 1978), are expected to continue indefinitely, and represent a serious handicap.