Maine was not the first state to face a class-action lawsuit seeking to improve conditions at a state facility for the developmentally disabled. Some 48 such cases were filed between 1971 and 1996.

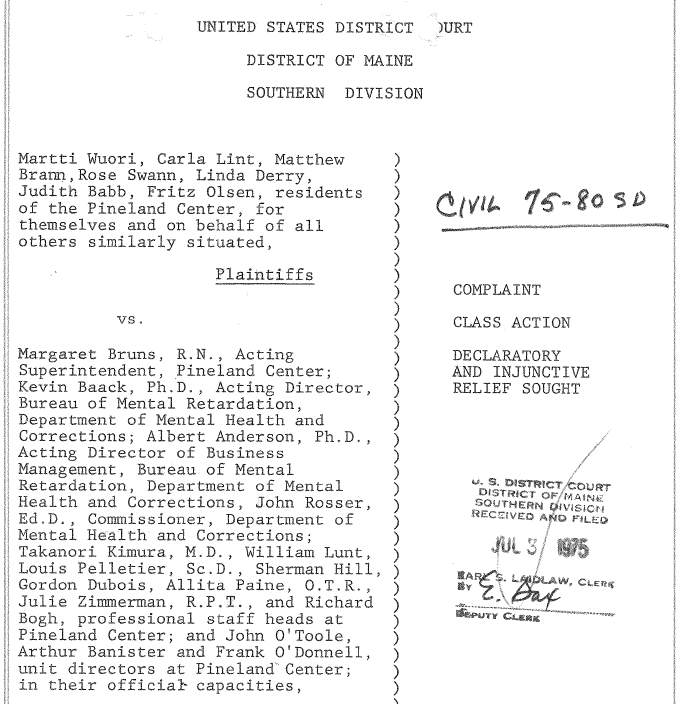

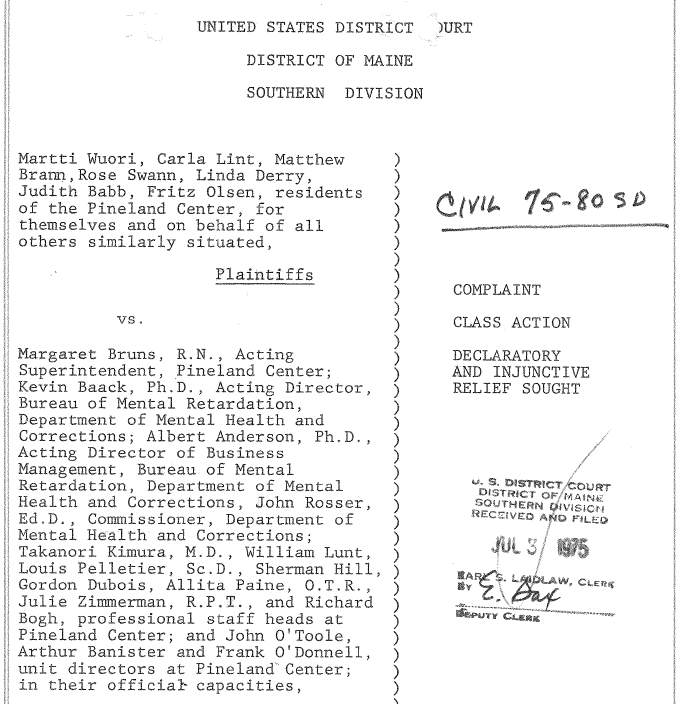

Maine’s case, Wuori v. Bruns, filed in federal district court in Maine on July 3, 1975, – by Pine Tree Legal Assistance, the first organization in Maine to provide free legal assistance to those in poverty – acknowledged that changes were underway at Pineland, but that the six defendants named in the case, and the “class” – all other residents and future residents – were not getting “training and education which would enable them so far as possible to lead normal lives.”

The suit stated, “Instead, acute boredom, physical deterioration, social regression, psychological debilitation, severe depression, and low morale predominate.”

The plaintiffs ranged in age from 15 to 62 and had been at Pineland from 6 to 37 years.

The complaint detailed physical conditions at the institution, including crowding, lack of privacy, and limited choices for residents – as well as the physical and chemical restraints, lack of physical and occupational therapy, lack of education and recreation, and lack of speech and hearing therapy.