The U.S. District Court in Portland named a court master, David D. Gregory, to oversee the consent decree and monitor the state’s progress in reaching the deadlines and objectives to which it had agreed. Despite pleas from the administrators of the institution that they needed a $1.2 million budget increase to meet the requirements of the decree, Governor Brennan put $650,000 less in his 1979 budget than their request.

Neville Woodruff, the lawyer who represented Pineland residents in the lawsuit, threatened new suits against Pineland in early 1979, saying, “They are very far behind in three major areas – staffing, quality of programs, and staff training.” (Bangor Daily News, February 16, 1979) Court Master Gregory was critical of the lack of improvements at Pineland as well, saying in a March 1979 report, residents are “still just being kept. Life for them is purposeless. Some are locked into their living units…their access to fresh air is wholly dependent on the time and willingness of direct-care aides.”

Gregory’s second report in November of that year held similar sentiments. “Noncompliance is substantial and continuing…The environment in most residential and program areas is poor…Pineland does not provide anything close to the educational opportunities or individually planned programs promised by the decree.”

The administrators of Pineland shot back at the Court Master, claiming his report “clearly shows that the Master has abdicated his impartial judicial office and become an advocate for those who wish to close all institutions for the mentally retarded”. They objected to the “conclusion of the Master that Pineland Center must be closed”, saying, “Pineland Center is an essential element of the State of Maine’s system for the delivery of services to the mentally retarded….all person residing in the facility have been found…to be in need of the services available at the facility. In each case the State Court has certified that no less restrictive alternative is available which would offer a more suitable living environment.”

In June of 1980, Court Master Gregory recommended that the court retain control of Pineland for another two years based on his findings, but by November of that year, he reported that “Pineland Center is now taking seriously the community-placement needs of Pineland residents.” The problem was now, “not Pineland Center but a severe lack of suitable, often specialized homes, programs, and support services in the community.” His conclusions were that “the State has no system for collecting data relevant to decree compliance” and that there was a lack of “resource development” hindering placement in the community.

Pineland was released from court oversight in 1981, but the state did not meet the community provisions until November 1983. The court then ended its supervision of the decree, determining that the state was in compliance.

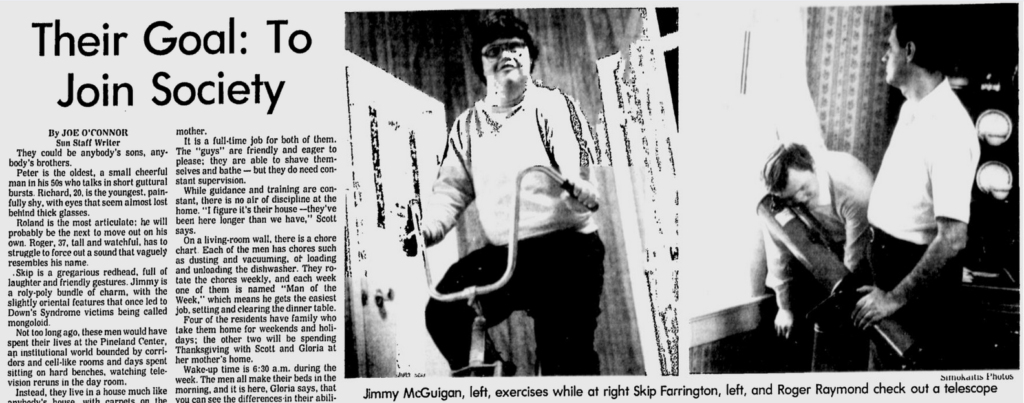

Several pieces were in place to ensure persons with developmental disabilities – at Pineland and in the community – received appropriate services, lived in appropriate conditions, and were able to exercise other rights outlined in the consent decree.

A nine-member Consumer Advisory Board made up of parents or relatives of residents, community leaders, the Pineland advocate and chaplain, and residents or former residents – was charged with “evaluation of dehumanizing practices, promotion of normalization, and examination of violations of individual rights.”

Each Pineland resident and person in the community had a correspondent – family member or an unrelated trained volunteer – to meet with them at least once a year, attend team meetings about their care and treatment, and report any problems to the Consumer Advisory Board.

A resident advocate at Pineland and advocates in each service region of the state were available to help with individuals’ concerns or issues and also try to assure their rights were not violated.