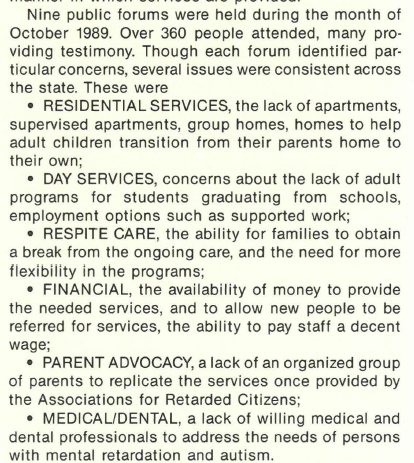

With public and policy sentiment turning towards the idea that people with developmental disabilities deserved the right to care in their communities and a full life with control over their choices, a new system needed to be built from the ground up.

Since the 1970s, boarding and foster homes focused on people with developmental disabilities had started popping up, but they were often plagued by a lack of oversight that led to abuses similar to what people endured in institutions. A lack of vocational and habilitative services also meant that while people might have housing, they didn’t have opportunities for full lives with interesting activities and connections to others.

Many parents complained of the “dumping” of Pineland residents, some going as far as to suggest that Pineland was better than the alternatives.

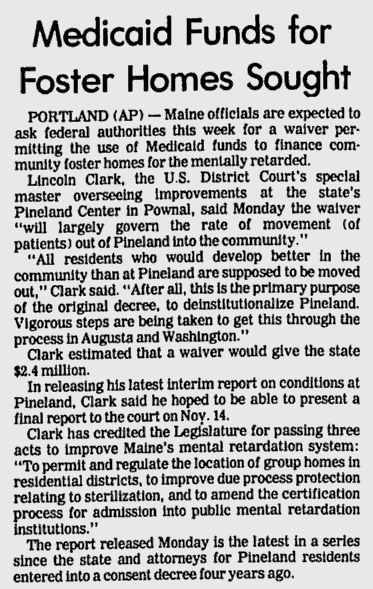

Another issue that arose at this time was that of “institutional bias”. Because of the way that Medicaid funds are given to states to pay for services for people with developmental disabilities, any services provided in the community must be funded through a waiver – in short, institutions are still the norm, and community care must be given as an exemption. This bias continues to this day.

Across the country, states were struggling with deinstitutionalization both for people with developmental disabilities and those with mental illness. The new system of community services developed slowly, in stops and starts, and issues of underfunding and lack of staffing continued. But despite the flaws, people with developmental disabilities began to have options for life outside of Pineland.