As a way of explaining and justifying the increasing disparity between rich and poor in industrial societies, Herbert Spencer of Britain and William Graham Sumner of the U.S. theorized that Charles Darwin’s laws of natural selection, applied to humans – and that progress was a result of relentless competition for survival. Spencer called it “survival of the fittest.”

Those who got rich from the rampant capitalism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the “fit” – people who had adapted to their environment and therefore deserved their wealth.

The theory became known as social Darwinism and included the idea that helping the poor or otherwise disadvantaged – by putting any restrictions on businesses or their practices – was going against the laws of nature and was, therefore, dangerous.

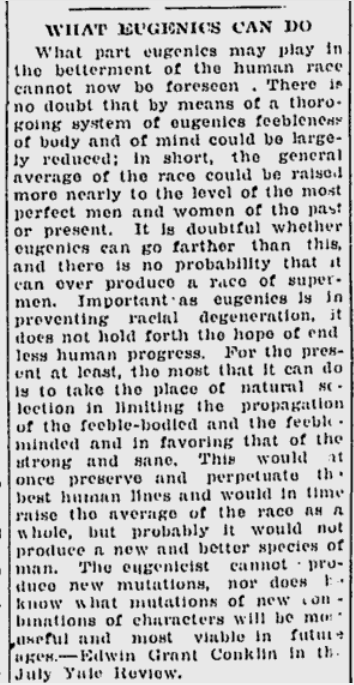

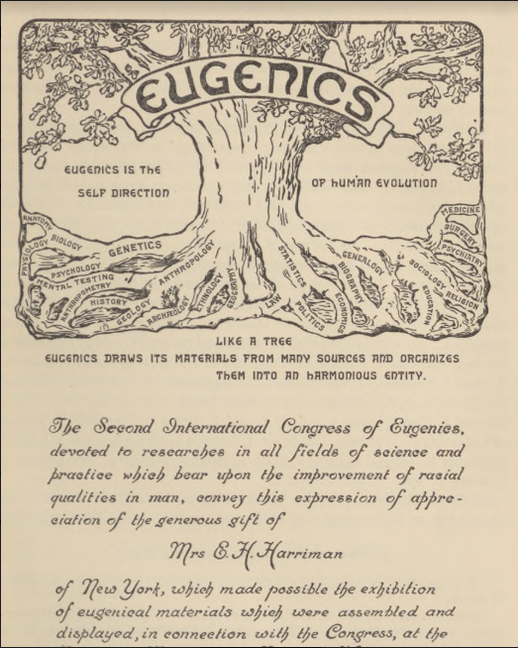

Eugenics – the belief that the type of “selective breeding” sometimes used with animals was appropriate to humans and that only the “best” people should reproduce – often accompanied social Darwinism.

Literally translating as “good creation”, the word Eugenics was coined by Francis Galton in 1883 in his “Inquiries into human faculty and its development”. Galton, setting a stage that led both to institutionalization and the Nazis, writes in that book: “The hereditary taint due to the primeval barbarism of our race, and maintained by later influences, will have to be bred out of it before our descendants can rise to the position of free members of an intelligent society”.

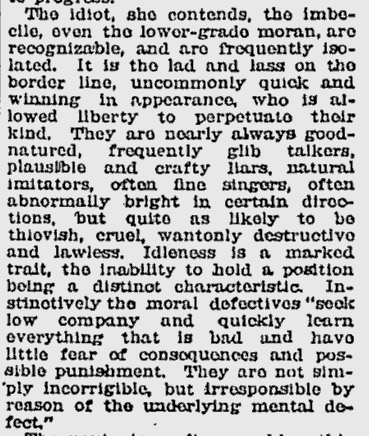

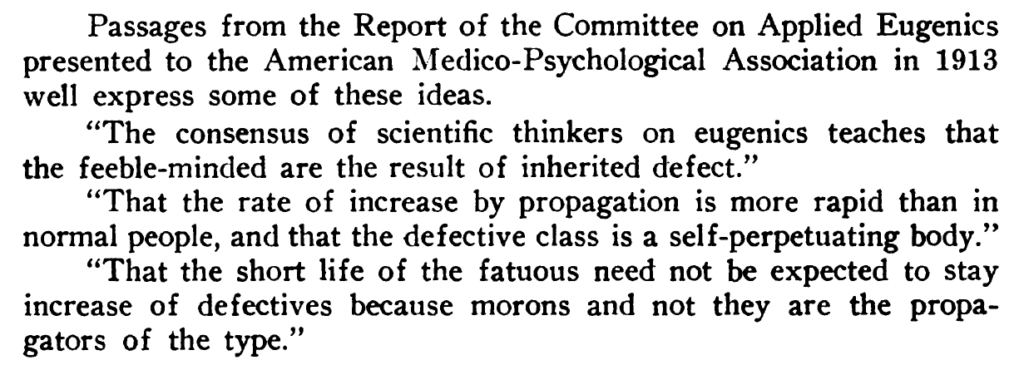

Alongside blaming heredity for causing intellectual disabilities, those with such disabilities were demonized and blamed for all the ills in our society – women of “feeble mind” were said to be promiscuous – and of course would “breed” more generations of “defectives” with their loose morals. Poverty was blamed on genetics, as was drunkenness and violent tendencies.

The theories drove much of what happened at Pineland until the 1940s.

By the early 1900’s, Eugenics had become a mainstream idea, supported by doctors and scientists of the day. In 1914, The Journal of the Maine Medical Association published an article entitled “Sterilization of the Unfit” by Henry M. Swift, MD, which argued that to reduce the number of “defectives” in society, and lessen the “public burden” such people present, “measures could be adopted to prevent propagation among these classes” – namely, involuntary sterilization.

From Dr. Swift’s article:

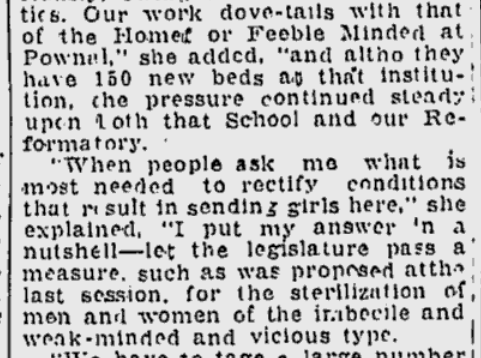

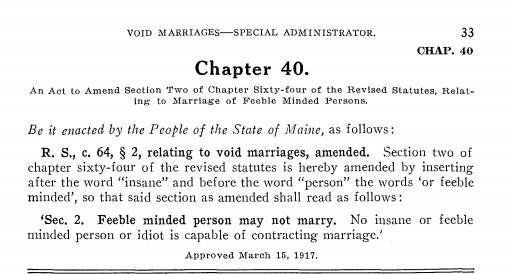

In order to keep the “feeble minded” from reproducing and passing their afflictions to subsequent generations, in 1917 the Maine Legislature made it illegal for them to marry as well.

Eugenics theories continued to gain traction across the country, and by the 1920s policies allowing involuntary sterilization had gained widespread approval.

In Maine, superintendents of prisons and institutions and other members of the public began to call for a law and public policy on the sterilization of the “feeble minded”.