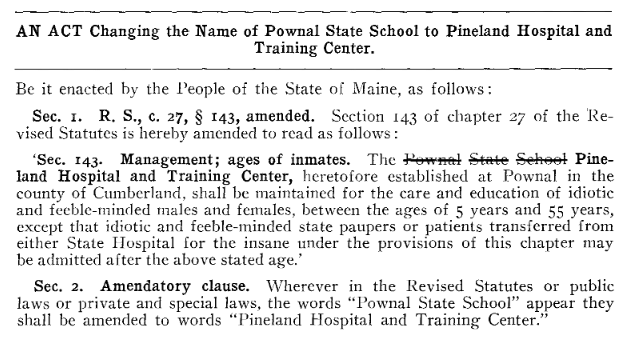

Superintendent Bowman was a proponent of the “medical model” of disability, which emphasized diagnosis and treatment of the individual over a systemic focus – people with developmental disabilities during this time were classified with words like “incurables” and “trainables”. He envisioned a diagnostic and research facility where the disabled could be cured or “fixed.” A name change in 1957 to Pineland Hospital and Training Center reflected his focus.

It is certainly plausible that this name change was influenced by the exposed abuses and neglect of the several years before – changing the name allowed the institution to have a fresh start, and the inclusion of the words “Hospital and Training Center” gave a veneer of scientific progress.

Bowman believed that 40 percent of residents were “incurable” and needed custodial care, much of which was provided by “patients” labeled “trainable” and “educable.” He wanted to see higher-functioning patients get treatment and be released – but, like superintendents before and after him, he found that difficult as the higher-functioning residents were crucial as unpaid staff, caring for other residents, working in the kitchen, sewing, serving as maids, and doing farm work, among other tasks.

But scientific progress costs money. The same year Pownal became Pineland, Governor Muskie proposed and got passed a sales tax hike from 2% to 3% – which was used to expand state services, including institutional care. In the next few years, the Maine Legislature would appropriate funds for a new infirmary at Pineland, underlining the evolving view of the institution as a state-of-the-art medical facility.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Pineland added various physical and recreational therapists, social workers, clinical psychologists, built a gymnasium, expanded education, field trips, and other activities. Change was happening, including some residents being released into the community, although they often lacked necessary services and support.

But the hospital also experimented with tranquilizers and other drug therapies and used the residents for various types of research on what might ameliorate their disabilities.

The Pownal Parents Club that had formed in 1953 pushed for better conditions and better treatment for residents, and lobbied for sufficient funding.

Bowman cited “widespread indifference of the general public to meeting the needs of the retarded in any other way than by consignment to a remote institution.” But the public had been largely kept away from Pineland and taught to fear its residents during much of its history.

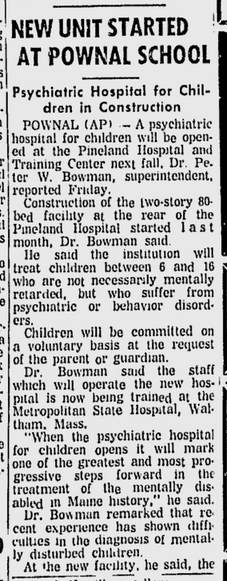

A new children’s psychiatric unit was also opened in 1961, with Dr. Bowman promising, “it will mark one of the greatest and most progressive steps forward in the treatment of the mentally disabled in Maine history.” (Lewiston Daily Sun, December 3, 1960) Around this time, Bowman himself began to express the view that many of those at Pineland could and should be returned to the community: “the mission and objective of Pineland is to return to the family, the community, and to outside civilization as many of the patients as possible, after they have received the maximum training and education we can provide here.” While he still viewed Pineland and institutionalization as a vital part of “treatment”, he argued that, “they should, if at all possible, be given a chance on the outside to have some semblance of meaningful existence, restricted as it may be.” (Lewiston Evening Journal, December 8, 1960)

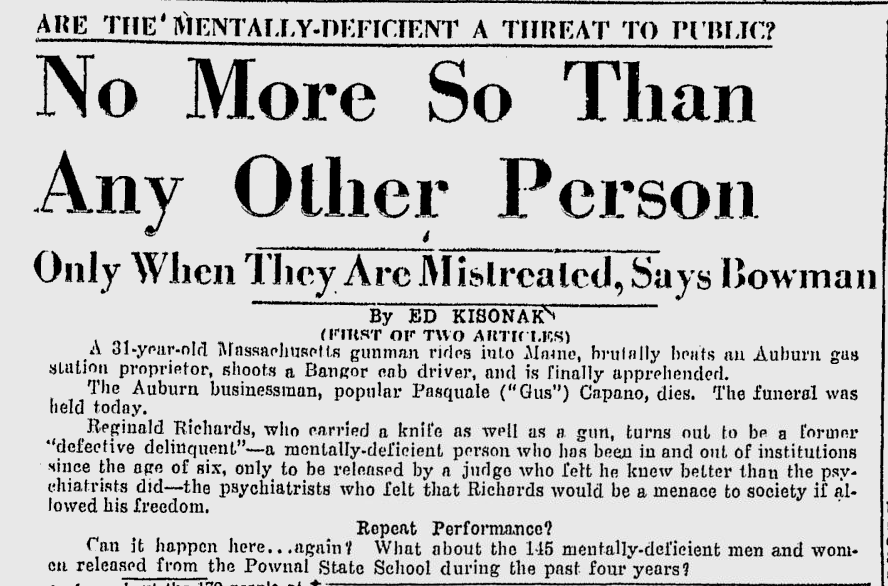

There were fears among the public that people with developmental disabilities could be dangerous if allowed to live in the community, spurred on by stories of former “defective delinquents” going on criminal rampages, but Dr. Bowman assured the press that “low mentality…has little, if any bearing on criminal tendency” and that “the release of persons from Pownal is no casual affair”. Bowman in this interview also admitted that residents of Pineland were treated as “slave staff” – used to care for their peers with more profound disabilities and “had to be kept on to help train new inmates”. (Lewiston Evening Journal, March 19, 1957)