The late 1920s and early 1930s were a time of great expansion for the newly dubbed Pownal State School – enrollment went from 271 in 1919 to 780 in 1932. This growth was spurred by a continuation of the fears of people with developmental disabilities being bad influences on society, but also, as the Great Depression began, from a sense that families and communities did not have the resources to care for those with disabilities and that an institution would be the most efficient option.

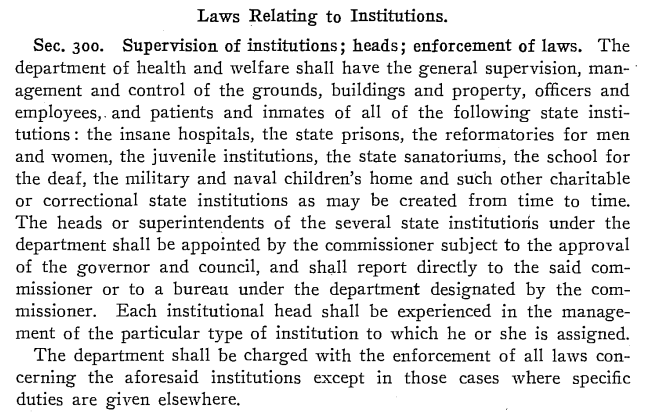

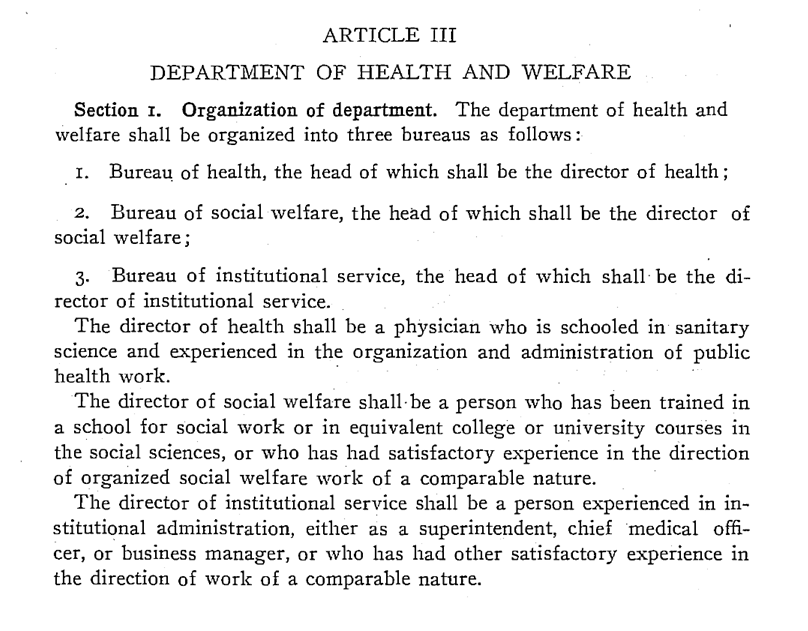

Alongside the growth of centralized institutional care for people with disabilities, the early 30s brought a parallel consolidation of governmental administration under the executive branch, beginning in 1931 with “An Act relating to the Administration of the State”, which created several new administrative departments, including the Department of Health and Welfare – in which the Bureau of Institutional Service would take responsibility for the oversight of all the state-run institutions in Maine, including being tasked “to license and supervise all institutions and agencies operating within the state for the care and treatment of defectives, dependents, and delinquents”.

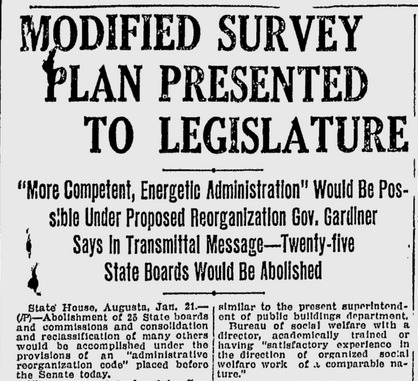

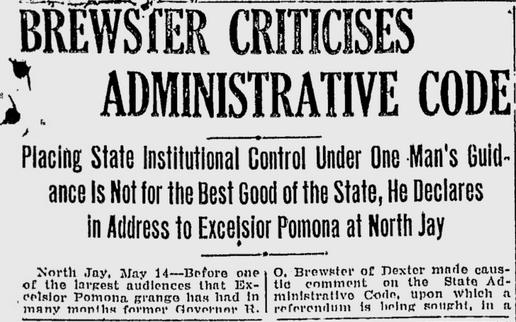

Governor Gardiner claimed that such a reorganization would lead to a “more competent, energetic administration”, but the bill had its detractors in the Legislature, who saw such a move towards consolidation as government overreach.

“The danger, therefore, which is threatened by the consolidation of departments and the appointment of commissioners and bureau of chiefs is placing too much money and political power in the hands of a few individuals. Another danger, as I see it in the bill, is that the authority conferred upon these administrative boards and bureau chiefs is an unlimited authority. The jurisdiction to deal with particular subjects involving the conduct of individuals is conferred in terms which are so indefinite that we will have to resort to the courts for a construction of the limitation of authority and power granted in this bill.” – Representative Farris of Augusta, March 31, 1931

The plan also had its support:

“Mr. Speaker and members of the Eighty-fifth Legislature: I am well aware that the lassiez-faire policy in government prevails in certain quarters. The bill which we have before us under discussion is nothing but a simplification of the fiscal program of our beloved State of Maine It has not been drafted under cover. The Cole Committee, in 1921, recommended these changes. This bill has been worked upon for six months, and by some of the ablest people of the State of Maine, and I for one am willing to accept their judgment as to the constitutionality of the law.” Representative Briggs of Caribou, March 31, 1931

In the end, the bill passed, and the Department of Health and Welfare was created.

In 1933, another law was passed establishing the organization and duties of the Department of Health and Welfare, and giving it much power over the institutions in Maine.