Change and reform were in the air at Pineland in the 1960s and 1970s.

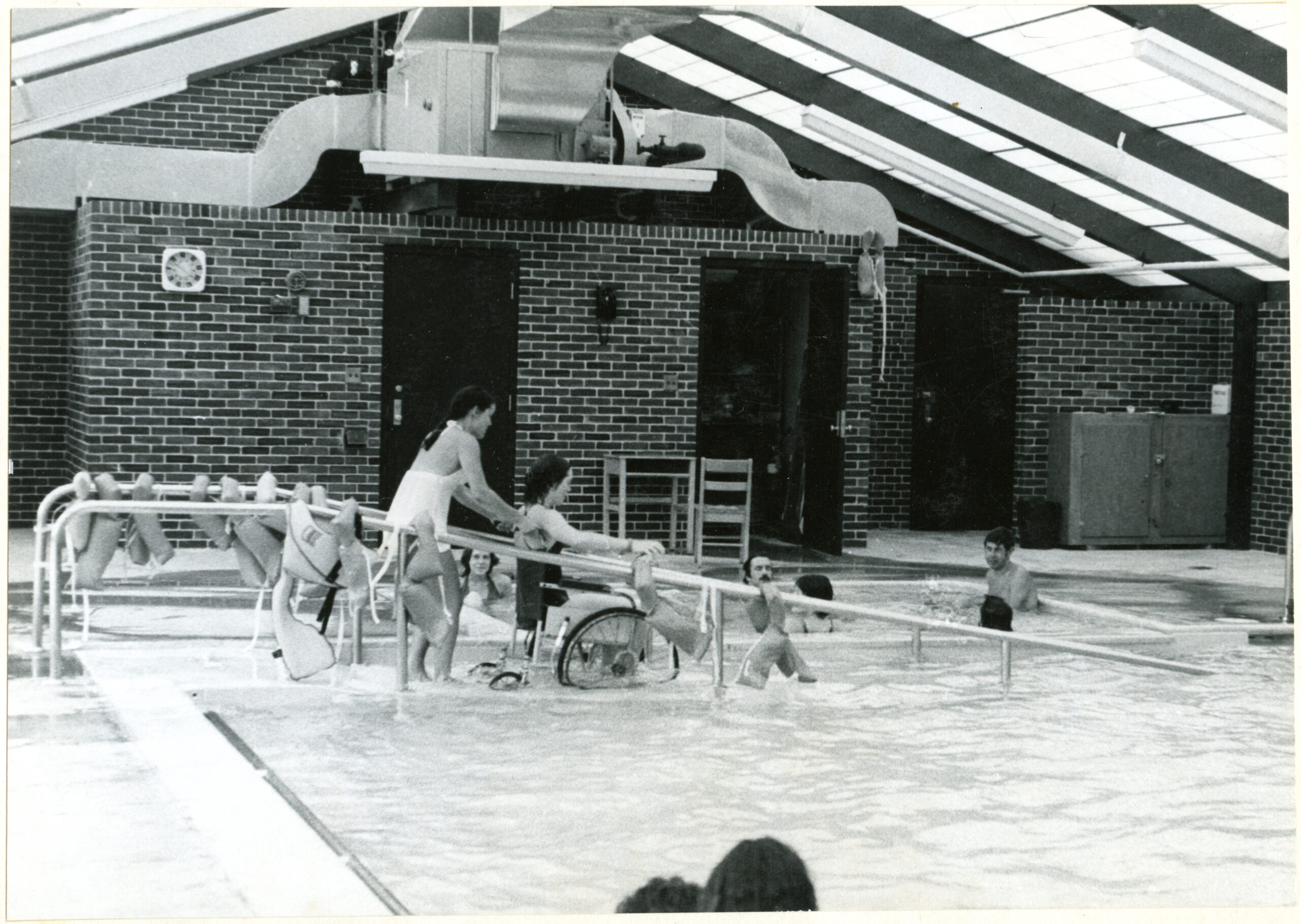

Superintendent Robert Bowman saw medicine, psychology, sociology, various therapies, and recreation as ways to help persons with disabilities.

The institution reached its largest population, 1700, in the late 1950s, before falling to about 700 by the early 1970s. The two farms, which had provided food and where many residents had performed unpaid labor, closed in 1961 and 1967. Buildings were renovated programs added and a gym and swimming pool built.

But Bowman, his ideas and those of staff he hired weren’t always popular – with parents, with staff, or with some officials.

In 1969, he hired Albert Anderson Jr., a psychologist, who later became director of the state’s Bureau of Mental Retardation. Anderson introduced “normalization” – this was an emerging theory on disability that called for the acceptance of people with disabilities and giving them the same choices and conditions as other people. Anderson later said the severely and profoundly disabled had been “treated as less than human.”

Anderson worked to change that. He trained staff and college student aides to teach toilet training, other personal hygiene, self-feeding, and other skills to even the most profoundly disabled, who also were given new clothing and shoes. One parent said her daughter learned to tie her shoes when she was 18 or 19.

Residents had more access to speech and hearing clinics, to rehabilitation programs, to physical and occupational therapy, and to education.

Despite some new ideas and improvements, problems continued. – many of which were highlighted in a 1973 site visit, the buildings were deteriorating and not suited to current needs, residents made few or no decisions for themselves.

Pineland, it noted, was trying to move from a medical model to a training model.

Staff, although dedicated and “with a genuine interest and concern for clients,” had little training appropriate for the changes, salaries were low, and communications between administration and staff poor.

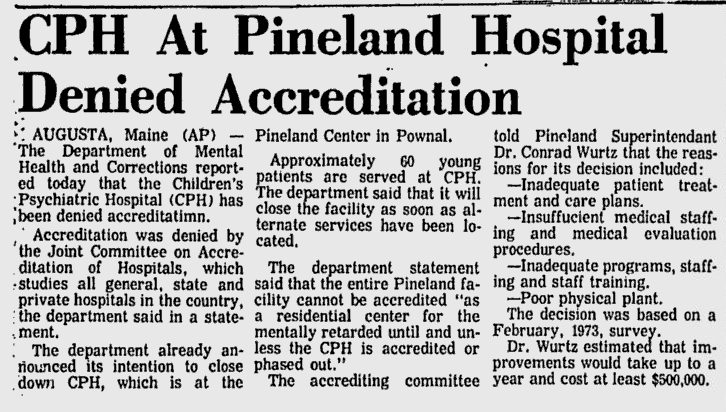

In May of 1973, the Children’s Psychiatric Hospital at Pineland was denied Federal accreditation, putting the entire institution’s status at risk. The CPH closed shortly thereafter.

For 23 years after the legislative committee’s report, Pineland continued to change, face issues with philosophy and deteriorating buildings, and confront anxieties about it closing, as the calls for deinstitutionalization grew.