The Maine Legislature, as such governmental groups have the customary behavior when faced with intractable systemic problems, on the recommendation of the Legislative Research Committee in 1955 created a Governor’s advisory committee to study the issue – the Maine Committee on Problems of the Mentally Retarded. “This committee, which is state-wide in its scope, will seek to survey the numbers and needs of the mentally retarded, both present and future, to compare the needs with what is available to fulfill them, to develop an integrated program coordinating both State and local programs, to inform the citizens of the State on various aspects of the problem, to report to the Governor, and to be of assistance in making recommendations to the Legislature.” (Lewiston Daily Sun, January 6, 1956)

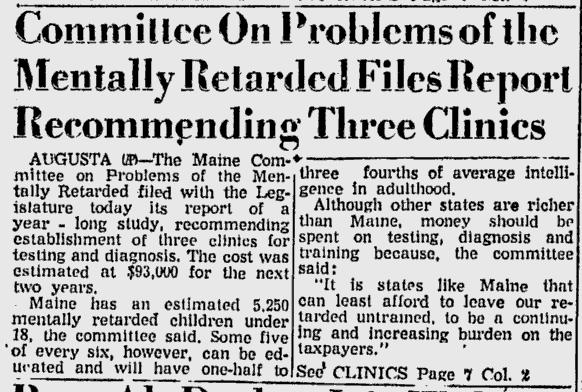

The committee filed several reports over the next two years, one recommending establishing clinics across the state to test and diagnose children – a sort of precursor to early-intervention programs. “There is no need, and no possibility, for placing the vast majority of these children in institutions, the committee said. But there is a need for clinics to test their intelligence and health and recommend treatment and training.” (Lewiston Evening Journal, February 21, 1957)

Another discussion in this committee revolved around the creation of a state agency that would deal with issues around mental health and those with developmental disabilities. In those discussions, a new idea was floated – that people with developmental disabilities should not be sent to institutions as a matter of course, and that there might be a better way. “Maine’s program was seriously lacking in preventive work, and too fully centered on caring for people in institutions rather than on maximum efforts toward restoring them to society.” (Lewiston Daily Sun, February 15, 1958) This sentiment would begin to enter the rhetoric of policymakers more and more over the next decade.