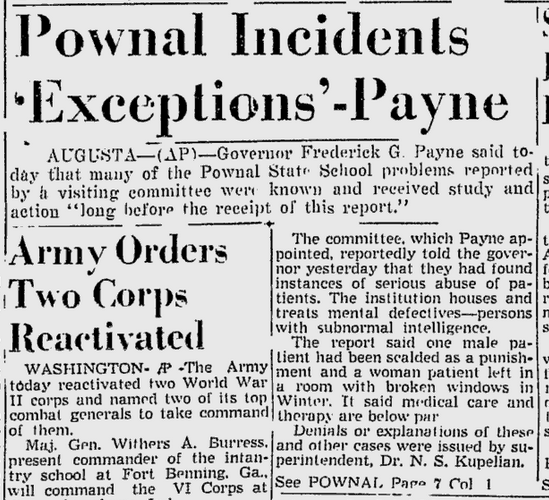

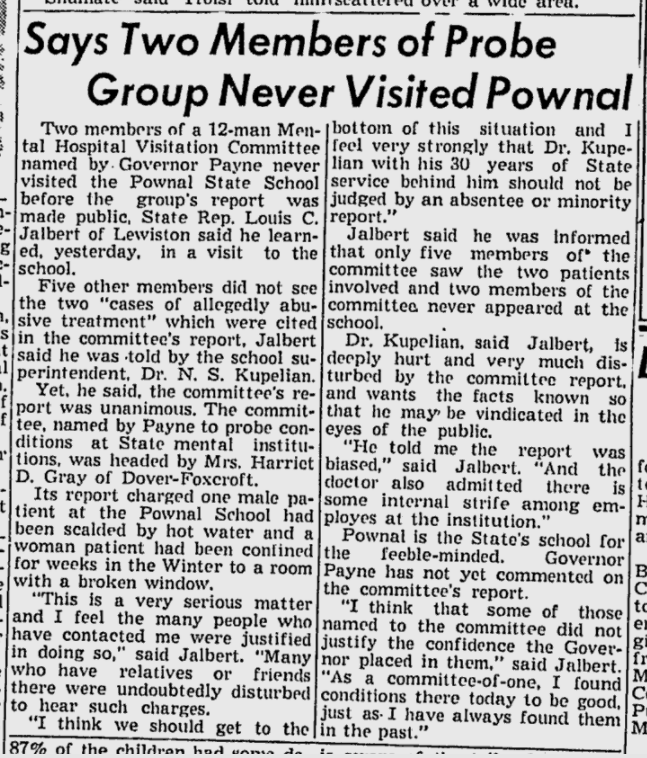

In the late 1940’s the Maine Federation of Women’s Clubs asked Maine Governor Payne to appoint a committee to look into conditions at Pownal State School, after their 1946 investigation found crowding and bad conditions. A Visiting Committee in 1951 cited cruel and abusive treatment, including excessive use of straightjackets, euphemistically known as “camisoles,” and physical punishments. They saw no evidence of rehabilitative work, but noted the facilities were clean. The superintendent challenged the findings, saying the committee was looking for negatives.

By the next year, Commissioner of Institutional Services Norman Greenlaw was attributing problems to “overcrowding” and pleading for more money, saying, “What goes on behind the closed doors of many of your institutions is to you, the average citizen, purely imaginative and fantastic, yet the standards of treatment have been determined by you…The money appropriated determines the quality of treatment.” (Lewiston Evening Journal, January 29, 1952)

The Legislature in 1953 “held the department of institutions to a tight budget” (Lewiston Daily Sun, 1/27/1954), not acquiescing to the Commissioner’s demands. They denied a request for a $5 million expansion of buildings. Commissioner Greenlaw continued to warn of wearing out infrastructure and a lack of qualified staff. That same year, a new superintendent would be given control of Pownal State School – Dr. Peter Bowman.

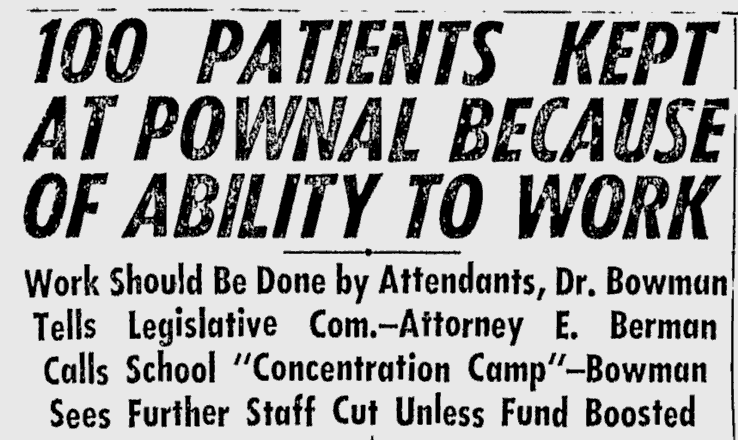

The next October, Superintendent Peter Bowman reported that some patients had been “scalded, beaten, and sexually abused in the recent past.” He fired some employees and the education director was suspended for sexually abusing clients. But, Bowman stressed, most employees were caring and tried to do the best for residents – but were hampered by inadequate facilities, and staff shortages. Bowman said, “I have been powerless to take complete corrective action because I need more help and better facilities.” (Lewiston Evening Journal, 10/15/1954)

Bowman also admitted that some of the abuses were due to patients being forced to care for other patients, due to staff shortages.

The Legislative Research Committee released its report in 1955:

The Committee’s recommendations for Pownal included a maximum security building for “criminal psychopaths”, additional living quarters for staff, a separate tuberculosis building, a school gymnasium, and added social workers and a speech therapist. The report also acknowledged, but didn’t look more closely at, the larger problem of institutionalization itself: